Baseball and Me

/Editor’s note: Our goal for this site is to raise topics that we feel are important…and to give you our point of view. The piece that follows definitely does NOT share that goal. Think of it more like sitting around with a couple friends after a couple beers…just spinnin’ stories…

THE GLOVE

I grew up across the street from a ten-acre public park in Chicago; it was always there, just down the steps from our modest house, serving as a baronial front yard. Our Dad figured this would serve the purpose of getting his two pre-school sons out of his hair as we got bigger and more rambunctious…and that’s exactly what happened.

We were freely allowed to roam the park, even at a young age—in those days, there was nothing unusual about this. One evening when I was seven, I returned home with the greatest treasure I could ever imagine—my own baseball glove! Someone had “lost” it in the park—and now it was mine!

It remained my most prized possession, by far—for about 18 hours. The next day, a Saturday, there was a knock at the door, and my Dad answered. I heard him call, “Don…come here.” With a man on the other side of the screen looking on, my Dad asked me, “where did you get that baseball glove?” I told him honestly that I found it in the park. The other man said it was his son’s glove…one he had just forgotten to pick up before going home. Mustering all my manliness and self-control, I went and retrieved the glove, and then handed it to this ogre on my front steps.

Then I ran upstairs where no one could see me…and sobbed.

This was life’s first taste of devastation for me. I got that glove fair and square…and no one even cared.

On Monday, my Dad got home from work and paused in the front hall, as he always did, to take off his shoes. Then I heard him call again, “Don, come here.” Now what?

And there it was. In his hands, glowing gold in both color and symbol, was a shiny new baseball glove. He said, “I thought you might want this.” It remained my constant companion for the next nine years, all the way through my sophomore year in high school. Eventually it turned almost black with dust and grime and criminal overuse.

There is no material item my Dad—or any Dad—could ever give that could be more treasured than that glove

Thanks, Dad.

CURVE BALLS

The rules for playing baseball around my house were pretty simple. If we wanted to play, we went across the street to the park. That’s why we lived there.

But there was one exception, and that’s when my Dad got involved. Then we’d play catch on the sidewalk in front of the house after dinner. Not only was it his only choice of physical exertion, it also gave him the chance to show us how a baseball could actually be curved in flight. He’d spin one and laugh when we had trouble catching it, and then we’d beg him to show us how he did that. Of course, we’d fail miserably when we tried, and the ball would go flying well wide of him or high over his head…and off we’d go, down the block retrieving it. We got a lot more exercise than he did.

However…on some really hot summer weekdays…my brother and I would break the rule and play catch ourselves in front of the house when Dad was at work. And on one of those afternoons something happened that seemed physically impossible. Somehow, I threw a “special” pitch to my brother that wasn’t just wide of him—it went impossibly perpendicular—like driving down a straight road and suddenly having the car turn 90 degrees left. The ball shot right toward the bay window…and cleanly through one of the mullioned panes. Glass shattered, and my Mother flew out of the kitchen as fast as the ball flew in.

“What did you do!? You just sit right there in that chair until your Father gets home!”

Uh, oh. That 90 minutes seemed like it took nine weeks. But at least it gave me a chance to think; not only about my possible punishment, but also about my defense.

Of course, Dad quickly spotted the damage when he got out of his car. He walked in, asking sternly, “what the hell happened here?”

I paused…looked up…and said, “I know my rights. No matter how mad you are, you have to take care of me until I’m 16!”

He blinked, shook his head, and I think stifled a laugh. “OK, you’re grounded for three days. Now, clean up the rest of the glass and you’re going to pay for the replacement from you allowance.”

I beat the man!

And I guess it just shows that radical troublemakers are born, not made.

LITTLE LEAGUE

Let me tell you about Little League. Tryouts at age nine may have been the most terrifying minutes of my life. To prepare, one of my friend’s Dad took a few of us over to the park and hit us impossibly high pop fly balls. We took turns missing them by yards either front or back, left or right. Eventually we could at least get part of a glove on one…and finally actually catch one or two. But could we ever make a team?

Somehow, we did. I was one of those kids that grew early, 5’9” by age 11. I gained confidence. Often in those days, coaches would designate one kid to pitch the first three innings, and another the last three. But one night—only slated for the last three--I told our coach before the game this was a terrible idea. I could feel I had it that night—no one could get a hit off of me! Didn’t matter. Last three innings, that was that. And in those three, none of the nine kids facing me got a hit—hardly hit the ball at all. I struck out seven of them. It left me both happy but frustrated, and for the first time I asked, “why don’t people listen to me?”

Later that summer I was the starting pitcher in an all-star game. But before we started, the opposing coach protested. I was so tall, he said, “that kid could reach out from the mound and tickle the noses of our batters!” He demanded a birth certificate to prove I wasn’t already a teenager. Uh, oh.

That could have been a real problem. But my Mom produced one on the spot.

Thanks, Mom!

Lest this sound like braggadocio, let me relate the most legendary moment in my Little League career.

As a pitcher, I threw the ball hard, but like a lot of kids, I didn’t always know exactly where it was going. In those days, there were rubber home plates where the batters stood. Those plates sat on top of the original wood ones which had been implanted in the dirt when the field was originally laid out. Over the years, they had eroded to the point where they were all but invisible. So, the rubber ones stood almost an inch high off the ground with beveled 45 degree edges, so that players running or sliding wouldn’t be obstructed.

Also in those days there was one umpire that all the kids hated—old-man O’Malley. Like most Dads, he was a veteran of World War II, and was one of those who believed boys needed to be taught to be men from the earliest age. Thus, he was “grouchy” at best, and often curt and dismissive. He didn’t make calls so much as he gave orders.

And he was behind the plate when I was pitching one night. I was in the middle of one of my wild streaks and getting madder—and throwing harder—the more frustrated I got. So it was that I let go of one blazing fastball that came in low—VERY low. And at full force it struck the 45-degree bevel at the edge of the front of the plate and shot up, right past the catcher, and somehow right beneath the chin guard on the old man’s facemask.

Struck directly in the Adam’s Apple, O’Malley went down like an oak. The crowd groaned…and some of the kids cheered beneath their breaths.

He eventually arose and continued the game. We lost.

But afterwards, some of the kids came up and said, “nice pitch!” Like I had planned it.

Hamilton said, “man is destined to be ruled by accident and force.” Sometimes, the force of a misguided fastball can make you ruler for a day.

BROTHER ACT

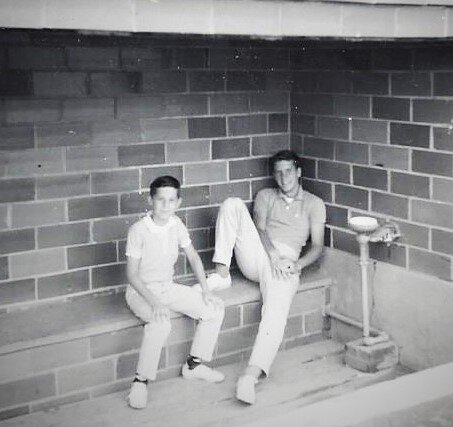

What binds brothers together? In our case, baseball. (In photo, sitting in dugout at Doubleday Field, baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY)

I was always big for my age; back then, he was small. (However, today, he operates at an elevation a couple inches higher than I do.)

But that didn’t stop the baseball competition between us. Sometimes it was wiffle ball in the backyard. (Yes, again blatantly playing on property my parents owned rather than the public park across the street. But we knew a whiffle ball couldn’t break glass.)

And another form of competition continued all winter long, thanks to a card and dice game called APBA Baseball. Here’s how it worked. Two dice were tossed from a cardboard cup, one slightly larger than the other. The number from the bigger die was read first. Then, the combined number rolled—anything from “11” to “66”—was calibrated against a specific playing card for every major league player. Each card was adjusted so that a certain number for one player—say a “23”—might result in a different result than for every other player in your lineup. Better real-life players got better outcomes. Think of it as sabermetrics before computers. It was so detailed that there was even an extremely rare result which would have your game “rained out”. We kept score for every game we played and recorded the results religiously.

But there were problems. Our biggest threat was the fact that the cardboard dice cup had a metal bottom. We rattled the dice aggressively trying to force a good roll. This happened well into the night and was not music to everyone’s ears.

One midnight we heard our Dad tromping up the stairs. Never a good sign. He barged in and demanded, “stop that racket! I’m trying to get some sleep!”

Darn. Game over. Were we to be limited only to day games when he was at work?

Nope. The next day, my problem-solving brother came up with one of his devious solutions, producing some felt, and precisely cut a round piece that perfectly covered the metal bottom of the cup. The sound was muffled. APBA was revived. Dad got his rest.

Thanks, Bro!

ALMOST FAMOUS

One hot summer day a couple neighborhood buddies and I decided to go to the ballgame that night at Old Comiskey Park. So we hopped the bus and a couple trains and arrived to find a pretty lackadaisical crowd. The White Sox were playing the mighty Baltimore Orioles, who were running away with the American League pennant.

We sat down in our purchased seats in the lower grandstand, but it was too hot to be close to anybody. We looked out and up at the immense upper deck in right field. Not a soul was sitting there. So off we went. From up there, we felt like we were a mile away from the action, and masters of this domain—entirely alone.

In the second inning mighty Boog Powell, the burly Oriole’s first baseman, stepped into a fastball and launched one of the highest popups I’d ever seen. We looked down at the second baseman, figuring that’s about as far as the ball would travel. We saw him looking back towards us.

Then we looked straight down at the right fielder—maybe it was going to him. Nope. He looked our way, too. What?...

Suddenly we realize the ball apparently wasn’t coming down—maybe ever. There it was—still sailing over us!

Now, legend had it that Babe Ruth once hit a ball clear out of old Comiskey on the fly, never bouncing off the roof on the way. But that could never be confirmed. Now, maybe Boog had done it?

We heard a mild clank as it struck the roof, ricocheting off into the parking lot beyond. Heroic by any measure; but honestly, not historic.

About five minutes later a couple of winded sportswriters climbed up to us and yelled, “hey, kids, did you hear that ball hit the roof?!”

We looked at it and replied, “yeah—it hit.”

The sportswriters grimaced with disappointment and began their trudge back to the press box.

And with them went our chance at immortality. One little lie and we coulda’ had our names in the paper the next morning as expert witnesses.

It was a simpler time.

HIGH SCHOOL HEROES

During my sophomore year, I was the youngest kid on the varsity team. And that team was extremely talented. We played our way through the city qualifiers and wound up as Chicago’s representative to the eight-team state tournament, to be held in Peoria. Our game was broadcast back to Chicago on the radio. Big time.

About halfway through that season I had worked my way up to become the starting second baseman. But when the starting lineup was announced by the coach for that first state game, I was on the bench. The senior I had dethroned earlier had reclaimed his spot. I seethed but didn’t say anything. Like every teenager in history, I pondered how incredibly unfair life is.

As it turned out, I did get into the game as a “defensive replacement”, and crouched into position in the field, absolutely committed to doing whatever my team needed. I would run through walls; spike myself in the face. Didn’t matter. I was pumped!

And sure enough, the second batter up while I was out there hit a sharp ground ball to me. My brain was ready to react—but my body wasn’t. I was quite literally petrified with fear. Had I needed to move two feet to my left or right…to reach up or stoop over just a little to field a grounder…I could not have moved. I was as fluid as a statue.

But fortunately, the rock-hard infield directed the ball on two high bounces directly toward my belt buckle. The only move I needed to make was the one I did. I simply turned my wrist to catch it. I had so much time that I could have rolled the ball to first to retire the batter. But I was so amped that I actually caught the ball and, with maximum adrenaline flowing through me, threw it over to the first baseman at about 90 miles per hour.

He grabbed it but looked over to me and yelled, “what the hell are you doing?!”

I pretended like I didn’t hear him. We got the out.

It was a tense game, and we trailed 3-2 with just a couple innings left. But then we loaded the bases with two out and our best hitter came to the plate. Pee Wee was so adept at every facet of the game that he went on to play in the minor leagues for the Los Angeles Dodgers organization. The crowd screamed non-stop, reaching a crescendo when Pee Wee lined a rocket over the shortstop’s head that seemed destined to clear the bases. But…the shortstop leaped…the ball struck in the webbing of his glove…and the rally was over.

Pee Wee hung his head, deflated as he shuffled slowly toward first base. But the screaming only got louder. What Pee Wee didn’t see was that he hit the ball so hard that it shot through the shortstop’s glove…and began rolling into the outfield. He never noticed. We screamed at him to run…but he couldn’t hear us. The shortstop retrieved the ball…pegged it to first…and Pee Wee was retired, with no run scoring for us. That rally was over.

And an inning later, karma arrived. In our last at-bat, I was due to hit second, still down a run. But the coach decided to pinch hit with someone more experienced. (Maybe he noticed my petrified play in the field.) The pinch-hitter walked up to the plate and struck out. Damn, I could have done that!

The pinch hitter was the son of old man O’Malley…who I felled with that wild pitch back in Little League.

Two years later we were ready to win both the city and state titles. This team was even better than the version two years earlier. In the final qualifying game to go to state we had our best pitcher going, someone good enough to later be drafted by a major league team. By the fourth inning we were rolling, up 3-0. The other guys hadn’t put a man on base yet. One of the adults who had coached several of us on our summer independent team left in order to beat the rush hour traffic. He knew it was over.

Then there was an easy grounder to my buddy at shortstop. He picked it up cleanly and threw perfectly to our first baseman—another easy out.

But he dropped the ball.

OK, whatever. Just a regrettable way to lose a perfect game. So what. Then a bunt for their first hit. Then another one. Then a fastball that “sawed off” a little hitter…who defensively made contact on a pitch almost on his knuckles…but he hit it just forcefully enough to bloop over my head in front of the right fielder. Two runs scored. And so it went for several more batters. Nothing hit hard. But with enough good fortune so that a game we had “won”…was lost.

As I said, all teenagers know, life isn’t fair.

Well, there were still the semi-finals for the city championship--winner to square off at legendary Wrigley Field, where the Cubs play. We were the middle-class white kids from the outskirts of the city. Our opponents were black kids from an area that then, as now, ranks very high among the city’s socio-economic “hardship” neighborhoods.

In warm-ups they seemed disorganized, disheveled, and almost disinterested. This was going to be easy.

We played—and we also got played.

Once the first pitch was thrown, they looked entirely different. They were really good.

And on that day, better than us. Another dream died.

What I remember most about that game was the drive home on the bus. It was stop-and-go expressway traffic on a sweltering day. We were beyond despondent, miserable in every way. There would be a lot of disappointed people waiting for us when we got home. And it was our fault.

As we inched along haltingly, I suddenly heard tires squealing in the lane next to us. A couple of young guys going way too fast had slammed on their brakes—but too late. In front of them was a construction truck with two imposing iron I-beam girders protruding far out the back. I looked over just in time to see those I-beams crash through the windshield of the car—right at the heads of the guys inside.

Everything stopped. And then, a couple seconds later, both doors slowly peeled open…and the two guys staggered out. Back then, cars were big enough so that both dove toward the center of the large bench seat…and not restrained by shoulder belts, had enough room to avoid certain death.

Life is indeed unfair. But there are worse things than losing a baseball game.

THE BOYS

The two best friends of my life played with me on that team. One is two thousand miles away, the other three thousand. It doesn’t matter. We text, talk on the phone, and get together for baseball. One year it was the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Other times to see other teams in other cities; last year, Cleveland; this year, hopefully heading for Detroit.

Our lives have unfolded the ways most do. Pride in our families. Heartbreak. Some notoriety. It’s been more than half a century since we played together that senior year.

And even though there’s always a lot to catch up on, one thing never changes. We always—ALWAYS—talk about those two games we lost.

Youth is a crucible that both inspires and deflates. It’s where we start learning about the world.

And some of those lessons never escape us. Especially the ones that hurt.

COLLEGE

I felt there was still a lot of baseball ahead of me. I enrolled the next fall in the state university, and almost immediately got anxious about spring baseball tryouts. I needed to make that team.

One fall Saturday I went to the school football game and saw something from the other team I’d never witnessed before. The opposing punter, when he finished kicking the ball, wound up in an almost impossible ballet pose, with his kicking foot extended above his head. How could anyone do that?

When I got back to the dorm I told my roommate I was going to show him what I saw. I feigned kicking an imaginary ball and extended my leg as far up as I could. Unfortunately, I did not take into account that I was standing in my stocking feet on a linoleum floor. Predictably, both my legs shot up from under me, and then--effectively parallel to the floor--I fell flat on my back from about three feet up.

I was more stunned than anything. But a week later I tried to get out of bed in the morning, and I couldn’t move. At all. Something was very wrong. Over the next several months I got around, but most times not without a struggle. I went to the doctor and one said it was just a muscle pull. When that didn’t prove true, a second told me it was early arthritis. (At 18?). No matter, tryouts were approaching, and I wasn’t going to miss them.

I played pretty well. I was hitting, and in the field they moved me from my accustomed second base spot to third base, which is known in the sport as the “hot corner”—the baseball equivalent of a hockey goalie, since the ball comes at you so fast. One day at practice a hard grounder took a bad hop off the edge of the grass and smashed me under the eye, leaving me with a classic “shiner.”

When I told my Dad about it on the phone he said, “what’s wrong with you?”

I said, “nothing”—it was just a bad hop.

But he was right. It was something more. I stopped practicing because of the pain, and that summer they took me to the same orthopedic surgeons that worked with the Chicago Bears and the Chicago White Sox. It took the doctors about two minutes to properly diagnose what the others had missed. I had a slipped spinal disc, and if traction didn’t work, delicate surgery was the only alternative.

After the operation I sat in a hospital chair waiting to be picked up and realized that for the first time in almost a year, my back didn’t hurt. But the doctors also warned, “no baseball for a year—you need to heal.”

So I took the year off. And then starting in junior year, I had the chance to try out again.

I didn’t even bother.

I’ve always asked myself why…and I know there’s only one answer. I was scared. Scared that I couldn’t perform like I had before. Scared that the other players on the team had passed me by. Scared that I could no longer count on what had constituted so much of my identity.

I left the game I loved a coward. It still affects me to this day.

Maybe you can tell.

TWO HALL OF FAMERS

When I was a kid in Chicago, everyone knew how to identify a non-baseball fan. It was the guy who claimed, “I root for both teams.” Impossible. You were either a Cubs fan or a White Sox fan. You took sides. I’m pretty sure in that city there were more arguments about baseball than any other topic.

However…when it came to Ernie Banks…everyone truly was a fan. He was everything every baseball kid looked up to. Incredibly gifted, coupled with an impossibly sunny disposition. They called him “Mr. Cub”; but to everyone, even the White Sox fans, he was really “Mr. Baseball.”

Banks grew up in a family of 12 kids in Texas. He began playing in the Negro Leagues and appeared destined for the major leagues, but was drafted into the Army for two years during the Korean War. When he finally arrived in the majors, he did so with a bang, being twice named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. But he also set a dubious record: the most career games played without reaching the playoffs. No great ballplayer ever endured more disappointment. But he never showed it.

In 1977 he was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame. On the day of the announcement (not the ceremony in Cooperstown--the day of the vote count), Ernie Banks was the live guest at the end of an evening local TV newscast in Chicago. I produced that show, and afterwards the sports producer and I cornered him in a hallway to offer our congratulations. It was a great day for him…for baseball…and for Chicago.

After chatting for a couple of minutes we felt we were overstepping our bounds, and asked innocently, “well, what does a Hall of Famer do to celebrate on this big night?”

He looked blankly for a second and said, “well, I don’t know. My wife is out of town, so I guess I’ll just go home.”

The sports producer and I looked at each other and jumped. “Is there any chance we can buy you dinner?” Stunningly, he agreed.

So, we went downstairs to a distinctly downscale corner diner and ate with him…and talked baseball for two hours. I don’t know that I’ve ever had a more warm and charming dinner companion. He was an amazing human.

The only moment of discord came at the very end, where we began to argue about who would pay the check. This was our treat!—but he strongly disagreed. In the end, on the most momentous day of his storied career…Ernie Banks bought us dinner.

He was a Hall of Famer in every sense of the word.

When my second son was eleven, his most prized possession—by far—was his Ken Griffey, Jr. baseball card. Baseball cards were enjoying a resurgence then, and this was the biggest prize of the era. Nintendo marketed a video game called, “Ken Griffey Jr. Baseball.” We played it for hours.

One day I noticed that a group of Seattle Mariner players including Griffey was going to play a charity basketball game against the faculty of the local high school—a fundraiser which was a nice gesture on their part. I asked my son if he wanted to go. His eyes widened.

As we got seated in the bleachers before the game, the public address announcer said that there was still time to enter the raffle for an autographed Ken Griffey, Jr. basketball. I pulled out $5 and told my son he should go out to the lobby and enter. Being shy at that time, he demurred. But the idea of his hero’s signature on a basketball—maybe the only such thing in existence—finally won him over.

At half time, the winner was announced—and sure enough, it was my son. He scrambled down the bleachers to claim his treasure…but when he returned, there was a sad and puzzled look on his face.

“What’s wrong?”

“Well, I got the ball—but it’s not signed…”

I checked, and he was right. I was annoyed, but knew it was just a mistake. I told him he should take it over to Griffey right away—he was sitting on the bench on the other side of the gym, waiting for the second half to start.

“Just go over and ask him to sign it—tell him you’re the winner.”

Well, no one had ever asked him to do anything close to that bold in his life. He would rather jump into the Grand Canyon. But I persisted; this seemed like a “make him a man” moment.

So finally, he tip-toed around the court, walked up to Griffey meekly, and I could see them talking. But no pen emerged. So, he retreated up to the stands and informed me that Griffey told him to come back as soon as the game was over, and he’d do it then.

Neither one of us paid much attention to the game at that point. There was something bigger on our minds. With about four minutes left, Griffey was subbed out and went to sit back down on the bench.

And about 30 seconds after that, a back emergency exit door swung open behind the bench…someone stuck his head in and said something—and Griffey was gone in a flash.

He never had any intention of sticking around. My boy kept looking, waiting to see if the door would open again. It didn’t.

Afterwards, as people were filing out, he looked up at me and said, “Dad, why would someone do something like that?”

Some questions can’t be answered. Especially to an 11-year-old you love. But the moment did leave me with an unanswerable question of my own: how do you react when the loss of innocence for a son you treasure strikes in a single instant?

Griffey is a Hall of Famer--in a baseball sense only. He ain’t no Ernie Banks.

THE COMEBACK

I was 40 years old, in a stressful job in the middle of a stressed first marriage, when I saw the sign. It was a posting in a park seeking people to play in an “adult” hardball league.

I decided to try out.

I wound up on a team with mostly 20-something firefighters and EMT’s from my area. I was older, but we bonded over the ridiculous injuries that quickly cropped up among us, a bunch of past-due weekend warriors. Our shortstop became the first baseman because he couldn’t raise his arm as high enough to throw the ball overhand. I shifted over from second until pulled quads forced me to the outfield. Few could run full speed (and of course, the word “speed” here is relative).

We were the Bad News Bears all grown up—too grown up.

But I have to say this. One perfectly clear night, standing under both the lights and the stars in centerfield, I looked up and felt a surge of pure glee. It was the bliss of baseball. In that moment, I was perfectly happy…at total peace.

That one moment took me entirely back to Little League…to the ecstasy of taking part in something I felt I was meant to do. Just a glance looking up at the night sky. I felt connected to everything. Weird.

I am not spiritual, so I don’t have a frame of reference. It’s just that I’ve never had another moment like that.

THE NEXT GENERATION

In the shimmering mist of Americana, baseball is a passion that’s passed on from generation to generation.

I tried.

My twin daughters decided they would give the game a chance when they were day campers. I think they did it mostly for me. They played with a cushioned “hardball”. In their second game, a batter hit a soft pop fly to one of them in the field, and she dutifully raised her mitt to catch it. Somehow it avoided the glove entirely and landed on her forehead.

From that time forward, they retired from baseball and devoted their considerable athletic skills to soccer.

I took my second son, the Griffey fan, to a game in Seattle’s Kingdome one night, and we sat a couple rows behind home plate. At bat, one of the Seattle hitters lofted a high pop fly back behind him…and I could see instantly that it was headed right for me. (Since those Little League tryouts, I had learned to judge the trajectory of a fly ball.) I cupped my hands for the easy “basket” catch—and dropped it!

Fortunately, I reached down to my feet, picked it up, and handed it to him.

He didn’t care that I dropped it. He had a foul ball from his Dad. That’s what mattered.

One night many years later I went with my daughter (the one who had not been hit during day camp) to another Seattle game, this time in their sparkling new outdoor park. We were in the second deck, down the right field line, beyond the reach of any foul ball—and yet, here was one coming directly on a line toward us. It careened off the cement steps several rows down, and as I went to grab it just as it glanced ever so slightly off one of the metal handrails. It rocketed past my grasp then rattled against the seatback behind me. Damn!

I looked down to see if somehow it had miraculously fallen to my feet. Nothing. I had missed again.

Then my daughter laughed and said, “Don’t worry, Dad. I got it.”

And there it was, under her foot. Like the good soccer player she is, she had first trapped it with her shoe, and then stepped down to corral it.

She didn’t need her Dad to get a foul ball. She did it herself. And that’s all that mattered.

When my oldest son was just four, I took him to his first game at old Comiskey Park. He had only a rudimentary knowledge of the game, but his eyes widened like any kid’s when we walked up the steps for the first time and he saw the lights and the crowd and the impossible green of the diamond in front of him.

It was a night game and I figured we’d be there just a few innings…but we stayed to the end.

My little blue-eyed tow head never lost interest as he sat on my knee. He wasn’t the only one who found that night magical.

Over the years, I’ve somehow done enough to disappoint and hurt him so that he will not see me anymore.

I’ve lost him.

And yes, it cuts deeply.

But to my dying day, no one will ever take that sweet memory away from me.

I had him. He had me. And we had baseball together.

That’s all that mattered.

Have a comment or thought on this? Just hit the Your Turn tab here or email us at mailbox@cascadereview.net to have your say.